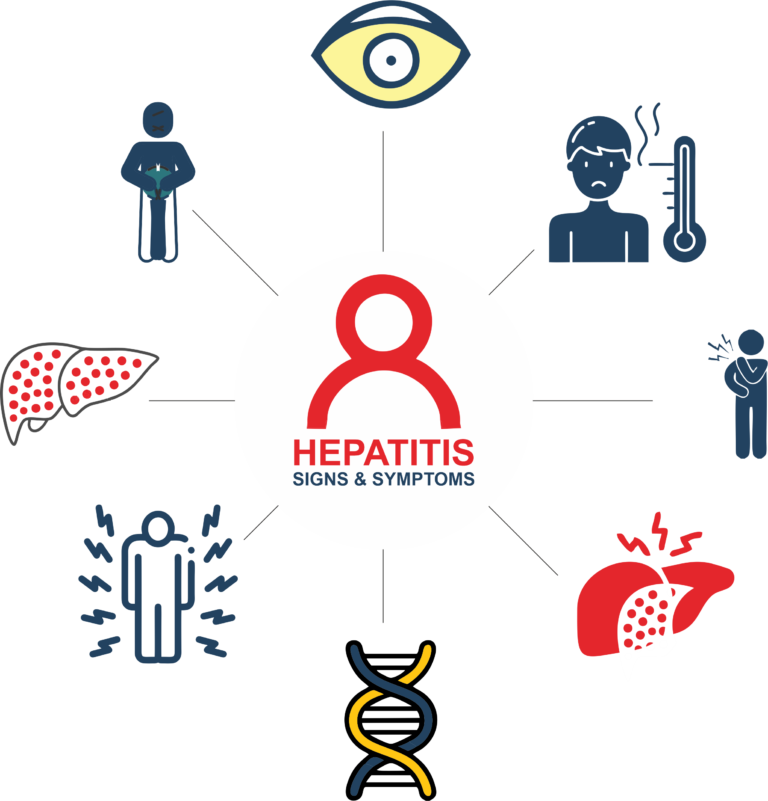

Hepatitis is described as an inflammation of the liver. It may be caused by drugs, alcohol use, autoimmune diseases or certain medical conditions. But in most cases, it is caused by a virus which is known as viral hepatitis. The condition of hepatitis can be self-limiting, or it can cause fibrosis i.e., scarring, cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Viruses that infect hepatocytes are considered hepatotropic viruses. Five hepatotropic viruses known to cause hepatitis, have been described and have been named as hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E in historical order of their recognition. Worldwide, cases of hepatitis presumably caused by viruses other than these five also occur.1 Hepatitis A and E virus are predominantly enterically transmitted pathogens and are responsible to cause both sporadic infections, epidemics of acute viral hepatitis (AVH) and are occasionally a healthcare infection prevention issue.2 Hepatitis B, C and D virus are blood borne pathogens which predominantly spread via parenteral route and are notorious to cause chronic hepatitis, which can lead to grave complications including cirrhosis of liver and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).3 HBV, HCV and HDV also pose a risk of healthcare-associated transmission or occupational exposure for healthcare personnel (HCP).4,5 The infection prevention of each of the viral hepatitis contains specific recommendations.

Viral hepatitis now ranks as the seventh leading cause of mortality worldwide. Although mortality due to communicable diseases has declined globally, the absolute burden and relative ranking of viral hepatitis as a cause of mortality has increased between 1990 and 2013.6

In South-East Asia, 100 million people are currently estimated to be living with hepatitis B, and 30 million with hepatitis C.7 In India, viral hepatitis is now recognized as a serious public health problem. It places a huge social and economic burden on the affected individuals, families, as well as the health system. Viral hepatitis is a cause for major health care burden in India and is now equated as a threat comparable to the “big three” communicable diseases – HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis.2 Around 400 million people all over the world suffer from chronic hepatitis and the Asia-Pacific region constitutes the epicentre of this epidemic.6

As per WHO and the latest estimates, in India, 40 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis B and six to 12 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis C. HEV is the most important cause of epidemic hepatitis, though HAV is more common among children. Most acute liver failures diagnosed are attributable to HEV.2 There are many challenges in prevention and eradication of Viral hepatitis in India.1 Maintaining adequate sanitary and hygienic conditions can help tackle the problem associated with enterically transmitted pathogens like HAV and HEV.2,8 Following a multipronged approach of active screening, adequate treatment, universal vaccination against HBV and educational counselling can help decrease the burden of liver diseases associated with HBV and HCV infection in India.2,8 WHO’s Draft Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis gives the much needed roadmap and targets to combat hepatitis. It provides realistic targets and action plans to eliminate hepatitis by 2030.2 This is planned to be achieved by building capacities in the existing health care delivery system to reach the desired goal.9

In May 2016, the World Health Assembly adopted the first global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis, 2016-2021. The strategy highlights the critical role of universal health coverage and sets targets that align with those of the Sustainable Development Goals.3 The strategy aims to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health problem by reducing new viral hepatitis infections by 90% and reduce deaths due to viral hepatitis by 65% by 2030.10 For World Hepatitis Day 2021, WHO is focusing on the theme “Hepatitis can’t wait” to highlight the urgency of hepatitis elimination with a view to achieving the 2030 elimination targets.10

Standard precautions, which encompass both universal precautions and body substance isolation, are appropriate for prevention and spread of all types of viral hepatitis in the healthcare environment.4 Vaccines are available for hepatitis A and hepatitis B. There is no vaccine available at the present time to protect against infection of hepatitis C & D virus; however, trials are currently underway. While there is a safe and effective anti-hepatitis E vaccine, at present it is only licensed for use in China. Given the recognition of HEV as a global pathogen, there is a need to develop HEV vaccines for use globally. Vaccines remain an important cornerstone in the battle to achieve dominance over hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E and thereby decrease morbidity and mortality from these infections in a cost-effective manner.12,13

1 Bhaumik P. Epidemiology of Viral Hepatitis and Liver Diseases in India. Ozkan H, Rahman S, eds. Euroasian J Hepato-Gastroenterology. 2015;5:34-36. doi:10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1126

2 Satsangi S, Chawla YK. Viral hepatitis: Indian scenario. Med J Armed Forces India. 2016;72(3):204-210. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2016.06.011

3 Liu Z, Hou J. Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Dual Infection. Int J Med Sci. 2006:57-62. doi:10.7150/ijms.3.57

4 Tomkins SE, Elford J, Nichols T, et al. Occupational transmission of hepatitis C in healthcare workers and factors associated with seroconversion: UK surveillance data. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19(3):199-204. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01543.x

5 MacCannell T, Laramie AK, Gomaa A, Perz JF. Occupational Exposure of Health Care Personnel to Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C: Prevention and Surveillance Strategies. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14(1):23-36. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2009.11.001

6 Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet (London, England). 2016;388(10049):1081-1088. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30579-7

7 Singh PK. Towards ending viral hepatitis as a public health threat: translating new momentum into concrete results in South-East Asia. Gut Pathog. 2018;10:9. doi:10.1186/s13099-018-0237-x

8 Kumar M, Sarin SK. Viral hepatitis eradication in India by 2080–gaps, challenges & targets. Indian J Med Res. 2014;140(1):1-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25222771. Accessed October 29, 2018.

9 World Health Organization. GLOBAL HEALTH SECTOR STRATEGY ON VIRAL HEPATITIS 2016–2021.; 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/246177/WHO?sequence=1. Accessed October 29, 2018.

10 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c

11 Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Linda ; Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings (2007). https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/healthcare-us/. Accessed October 29, 2018.

12 Ogholikhan S, Schwarz KB. Hepatitis Vaccines. Vaccines. 2016;4(1). doi:10.3390/vaccines4010006

13 Weinbaum C, Lyerla R, Margolis HS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of infections with hepatitis viruses in correctional settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm reports Morb Mortal Wkly report Recomm reports. 2003;52(RR-1):1-36; quiz CE1-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12562146. Accessed October 29, 2018.

Call us now

Drop us an email

Monday to Saturday